Making Nishiogi:

A Town in Between

An Urban Crossroads

(This article introduces the social history of Nishi-Ogikubo, or Nishiogi, a community on the western edge of Tokyo's Suginami district. Long thought of as an indistinct in-between crossroads, it gradually developed a local identity, associated with a human-scale streetscape of antique shops, second bookstores,, cafes, bars, and owner-operated restaurants. The question addressed here is how this local identity and local streetscape emerged.)

“Nishi-Ogikubo is a town in between, a town of intersections,” said Ōta Tetsuji, a Suginami City Councilor (Democratic Socialist Party) and resident barfly on Nishiogi’s Willow Alley. As Ota points out, Nishiogi was not a place at all until recently, but only a space in between other towns. Even today surrounding areas are more well-known: Ogikubo to the West, Kichijoji to the East, and Takaido to the South. So, when and how did Nishi-Ogikubo become an urban community? And how did it attain the status of a modestly famous neighborhood? This is a question of cultural narratives but also of material developments. This exercise in “deep Nishiogiology” goes beyond our usual focus on neighborhood foodways and takes us into demography and infrastructure—from migration history to schools and transportation. In general, it is about how any place is made, and more particularly how this set of rural Japanese villages became an urban Tokyo neighborhood.

The simplest answer to our question of how Nishiogi actually became a place is transportation infrastructure. Nishi-Ogikubo was a train station first, and a neighborhood grew up around it. The name “Nishi-Ogikubo” seems only to have come into wide use after 1922, when Nishi-Ogikubo Station was erected. Already by 1889, the railway passed through the area, (Kobu Railway, now Chūō Line) running from Shinjuku to Tachikawa, dividing the North and the South sides of the area. When Nishi-Ogikubo Station was established in 1922, other infrastructure developments followed. At first there was only an exit on the north side. The South Exit opened in 1938. Therefore, the development of the South side came a bit later, with the North being somewhat more commercial, and the South remaining more a quiet residential suburb. The unused land immediately next to the South Exit featured a black market after the war, attracting American GI's to the area and evolving into the post-war nightlife district.

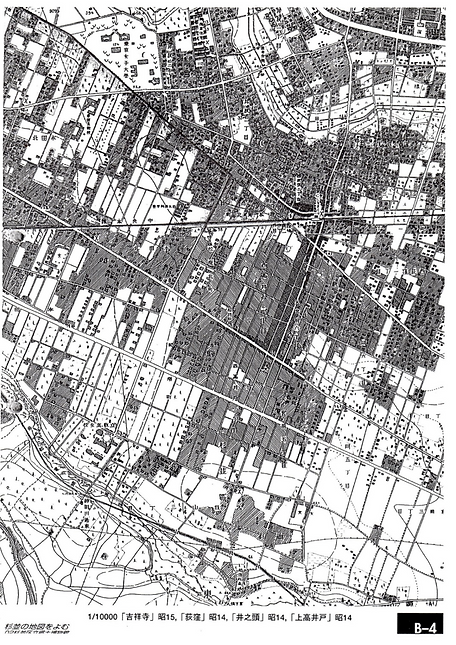

Naturally, Nishiogi Station did not appear in a map of the area from 1894 (see Figure 1a). You can see the names Kamiogi village, Shōan village, and Naka-takaido village, but there is no Nishi-Ogikubo. Farmland still comprised most of the area along the train line. In the second map from 1939-40 (Figure 1b) the farmlands have been replaced by buildings, and Nishi-Ogikubo Station is the center of a conurbation. We can see from these that the urbanization of this area happened largely in the first half of the twentieth century, though it is a process that continued afterward at a slower pace. Nevertheless, even in the twenty-first century, a few farms still remain in the area.

Figure 1 (a and b): Maps of the Area Around Nishi-Ogikubo Station 1894 and 1939

When the station opened, the surrounding area of the North Exit was part of Iogi village (Iogi-mura). Iogi village thus has the strongest claim to be the premodern forerunner of contemporary Nishiogi. This village itself was created in a merger in 1889 of four villages from the Edo period: Kami-igusa village, Shimo-igusa village, Kami-ogikubo village, and Shimo-ogikubo village. In 1926, through the reforms in urban administration, Iogi village (mura) became a town (machi) (Me de miru Suginami-ku no 100 nen). At that time, the south of the rail track, today known as Shōan was Takaidomachi. When Nishiogi Station was established, there were no buildings around the station. Kita-Ginza Street, from Ome Highway to Nishi-Ogikubo Station, was created to connect the town of Iogi to the station (from Me de miru Suginami-ku no 100 nen). Of course, there were no shopping or bar streets like there are today. This is evidenced in the photos published from that era in the book Seeing Suginami District Over a 100 Years (Me de miru Suginami-ku no 100 nen).

However, as Ōta Tetsuji’s comment suggest, a neighborhood does not simply grow out of a railway station. There was a complex story of urban place making both before and after the opening of the station. The patchwork “neighborhood of intersections” that emerged in this process still can be seen in its competing shrine festivals, the complex warren of neighborhood merchant associations, and the organization of fire and police districts.

First, let’s examine the shrines. The Shinto shrine is traditionally a place where residents gather together for an annual shrine festival, while incidentally giving expression to the boundaries of a local community. For centuries, there have been festivals at four locations around the station: Katsuga Shrine (founded around 1600); Ogikubo Hachiman Shrine (founded around 1100); Igusa Hachiman (the main shrine founded in 1664); and Shoan Inari Shrine (formally known as Enkouji Temple before it became a shrine in the Abolishing Buddhism Movement of the Meiji era) (Nishi-Ogikubo kankou techou). These are the four central shrines, with areas of jurisdiction divided among them long before the station became the center of the neighborhood. For example, Nakadori Street is under the jurisdiction of Ogikubo Hachiman until where Nakadori Street insects with Nittadori Street. Lively shrine festivals are still held in all these locations each autumn. This intersection of sacred spaces near the station shows that Nishiogi remains a place divided along traditional village boundaries.

Another way in which Japanese towns are defined is through the merchant associations organized along particular shopping streets (shoutengai). Here we also see more division than unity. However, we can also see the emergence of an urban neighborhood in the twentieth century. First, the newly established Tokyo Woman’s Christian University, founded in 1918, led to the growth of the shopping center from the station to the college along the “Woman’s University Street” or Northwest Street. Similarly, the foundation of the Nakajima Aircraft Company's Tokyo factory in 1924, where many military aircraft were produced. This modern factory prompted the development of commercial activities along the street heading northwards from the station on Kita-Ginza Street. After the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923 the evacuees from central Tokyo migrated to the area and stimulated the development of new shopping streets. This was a period of rapid urbanization. And in the immediate postwar era, people continued moving into the area, with merchant associations developing on the south side of the station.Today, there are more than 25 shopping streets in Nishi-Ogikubo.

A similarly complex picture emerges when we look at the jurisdictions of administrative organizations in the area. The Suginami Police Station was built in 1926 and with the expansion of the town, Ogikubo Police Station was founded in 1935 in front of Ogikubo Hachiman Shrine. However, a station for Nishi-Ogikubo was never established, just a modest police box in front of the train station. The Nishi-Ogikubo area is under the jurisdiction of both Ogikubo Police Station and Takaido Police Station. Therefore, according to Aukland Jeans Shop owner Tada-san, whose family has run a shop in the arcade on Nakadori since 1951, Nakadori itself is located on the jurisdiction boundaries of the two police stations.

Figure 2: Police Districts in Nishi-Ogikubo

Village to Town: The Taisho Era Migration to Nishi-Ogikubo

Despite Nishi-Ogikubo’s “in-between” nature, it was fully immersed in the rapid urbanization of western Tokyo in the early twentieth century, including the building of infrastructure and institutions. This development explains much of what transformed this area comprised of villages into an urban community. One man stands out in this story, and is a bit of a local hero now, with his bronze statue standing in the Zenpukuji Park. This was Uchida Hidegoro (1876-1975), the village head of Iogi village. In 1905, Uchida became the treasurer of Iogi, and in 1907 became the youngest village head in Japan. He was also known as the force behind establishing Nishiogi Station and paving Kita-Ginza Street after convincing the landowners living along the pathway. He was instrumental in both creating infrastructure to bring transportation, electricity, water, telegraph and telecommunications to the area, and establishing public facilities such as hospitals and schools (see the Appendix below for a timeline of Uchida’s biography). Details of these developments are in the appendix at the bottom of this report but you can see the network of the roads that developed on a map from that era (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Iogi Village in 1932: Roads near Nishi-Ogikubo Station.

In the Taisho Era (1912-26), the population of the area grew rapidly (see Figure 4). Western Tokyo’s population increase is often thought of in relation to the Great Kantō Earthquake that devastated Tokyo in 1923, prompting evacuees to flow into these areas, including what is now Nishi-Ogikubo. However, the story of population growth isn’t that simple, as can be seen in the case here. Nishi-Ogikubo Station was opened in 1922, a year before the earthquake. The creation of Kita-Ginza Street started in 1921. In the same year, electricity was installed. Therefore, even before the earthquake, the population growth seems linked to the development of urban infrastructure and urban institutions, not simply the evacuation from areas affected by the earthquake. In any case, modern infrastructure benefited and attracted these evacuees to the area. The Taisho period was really when Nishiogi became an urbanized community, not just spatially but also socially.

Figure 4: Population Growth in Iogi Village in the Taisho Period

In this period, while the population and number of households increased, the nature of work changed rapidly. People in various professions moved to the area. Later in 1924, the year after the earthquake, the population growth may have attracted the Nakajima Aircraft Company to open their Tokyo factory here. We can see the changes in the population structure by looking at the statistics from Iogi village on the North Side of the station.

Figure 5: Declining Agricultural Households in Iogi Village in the Taisho Period

In comparison to 1916, the number of farmers in Iogi village decreased in absolute terms by 21 households in 1925, and the ratio of farmers to the total number of households decreased by 44.97% from 67.83% to 22.86%. We can see that after the foundation of Nakajima Aircraft Company, the number of non-farmers dramatically increased (Figure 5).

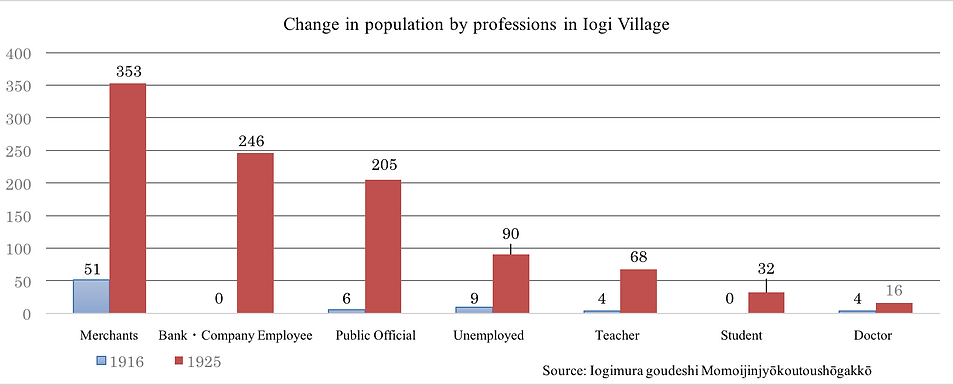

Figure 6: Changing Nature of Employment in Iogi Village in the Taisho Period

As shown in the graph (Figure 6), people worked in commerce as bank and company employees. There were also public officials, teachers, students, and doctors and thus, the period saw a sprouting of stores, banks, companies, government offices, military institutions, schools, and hospitals around the commuting area in Nishiogi. (The unemployed may have been comprised of housewives and elders. The cases coded under this category are unclear.)

Figure 7: Employment of Iogi Villagers in 1924

Although, farming was still the most common profession in 1924 (Figure 7), the proportion of people working in other professions was on the rise. The jump in the number of merchants, most likely working in the neighboring shopping streets, was the most obvious change. From the timeline in the appendix, we also can see that during this period, schools and hospitals were being built. Teachers, doctors, administrators and other professionals were needed in these establishments, so that even before the earthquake the area was urbanizing and the population was increasing. The establishment of the Nakajima Aircraft Company may have attracted evacuees to the area, furthering this dramatic population spike.

This is not to say that migration to the area was not accelerated by the destruction of the old city in the earthquake. In a chronicle of one of the oldest shops in the neighborhood, located in Nishiogi-Minami, the Mitsuya liquor store shopkeeper, Kamoshida Souichioro gives the following account of the store’s opening. “After the Great Kantō Earthquake, Nishi-Ogikubo became a newly developing area. With that in mind, we ventured into business. When you see the photos of the front of the store, you can feel the hardships my father went through…. Mitsuya liquor store faced a number of challenges. But, immediately after the Great Kantō Earthquake, the new areas in between Yamate (Edo’s noble uptown) and Musashino were developing, including the new residential areas in Nishi-Ogikubo. With the landowner’s agreement, new houses were built one after another and the number of patrons increased at the time.” (Mitsuya saketen no meibutsuoyajigakataru) Even after this urbanization, the neighborhood retained tell-tale signs of its rural past; for example, the neighborhood news circulars (kairanban) still were passed along among households according to the boundaries of former family farms.

According to shopkeeper Tada-san, the owner of the Aukland Jeans Shop on Nakadori, in the period after World War II, land was cheap and that enticed many people to move into the area. Also, after the war, in 1961, Fuji Industry, which took over Nakajima Aircraft Company, became Nissan’s Prince Motor Company. The people who worked there moved to Nishi-Ogikubo. They used the railway station and frequented the shopping streets. However, in 2001, the factory was moved and the area became Momoi Harappa Park. Business shifted again.

Becoming Nishiogi-jin: The Ironies of Nishiogi Pride

The development of the cultural identity of Nishi-Ogikubo is a trickier topic— one which requires more investigation. However, an emerging sense of “Nishiogi pride” seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon. In the postwar era, some restaurants and shops became a source of local identity. Nishiogiology has detailed some of these landmarks. The most prominent, for sure, is Kokeshiya, the first French restaurant that opened along the Chūō Line, where famous literati gathered in the immediate postwar era. Another very different face of local culture is the hippie counter culture found in Hobbit Village. The antique shops and old bookstores in the area now are probably the most widely shared source of pride.

However, the sense that Nishi-Ogikubo remains merely an in-between sort of place can still be heard in discussions with older residents. For them, Nishi-Ogikubo retains its prewar reputation as a wealthy suburb, once popular with company managers and military officers. As Ota Tetsuji pointed out to us, even in the 1960s and 70s, Nishi-Ogikubo was a neighborhood where chauffeurs lined up in the morning to drive managers to their offices in the city. We asked some elderly residents who have lived in Nishiogi for decades where they go out. “We go out away from Nishi-Ogikubo,” said one older woman. “I go to Ginza to eat delicious food. In Nishiogi, there aren’t any good tasty restaurants.” It seems as though some affluent residents do not have a strong identity as Nishiogiites (Nishiogi-jin), at least not an identity associated with the commercial spaces in the town.

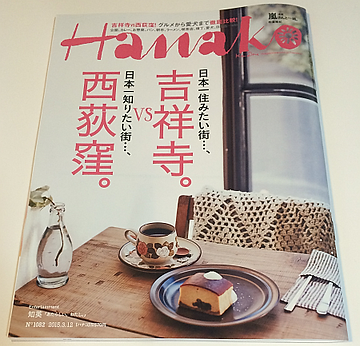

Nishiogi’s identity as a hip dining and shopping destination seems to have only been promoted quite recently by travel magazines and other media, with many focusing on the small restaurants and bars that have opened up in the past two decades. In March 2015, the magazine Hanako published an edition with the cover article “Kichijoji: The Neighborhood Japanese Most Want to Live in vs. Nishi-Ogikubo: The Neighborhood Japanese Most Want to Know About.” On the one hand, this title points to the in-between nature of the neighborhood, as a spill-over from Kichijoji. But, it also demonstrated the reputation of Nishiogi as a place worth learning about. Indeed, a sense of Nishiogi pride seems to be strongest among many people who have moved to the area more recently, and who enjoy and celebrate its “low city” (shitamachi) qualities, such as the small dingy watering holes along Willow Alley. Although not yet known as an expat destination, this may be coming too. Nishiogi has even made into the English press, with a feature on "eccentric Nishi-Ogi" on the TimeOut webpage.

As in other cities, it is these relatively young and highly educated newcomers who are both most enthusiastic about the town and most worried about its loss of distinctiveness. Many nouveau Nishigioi-jin express an anxiety about a creeping commercialization that threatens to turn Nishi-Ogikubo into a copy of its touristic neighbor, Kichijoji. There is even talk of a “Nishiogi bubble.” However, Nishiogi pride is not only nostalgia functioning as a defense mechanism, but also involves community-based NGOs, earnest study groups and nerdy local zines. This can be seen among the organizers and attendees of the Nishiogi Lovers Festival which began in 2016. These are some of the people who are studying and preserving local heritage, while creating an identity as Nishiogi-jin.

As in neighborhoods around the world, however, the same things that attract artists and intellectuals, attract development. Just this month, the Kikuya grocery store that has stood in a low-rise building front of Nishiogi Station since the war’s end in 1945 announced it would close. The aging of the owner and competition from a newly opened Kinokuniya supermarket inside the station building both were factors. Kikuya will be demolished, most likely to be replace by a new high-rise structure. For a long time, it was Nishi-Ogikubo’s in-between nature that saved it from the intense commercial developments of other well-known and larger stations along the Chūō Line, now characterized by high-rise shopping centers and chain stores. Nishiogi loyalists take pride in the station being the only one without a Starbucks. Yet, ironically, it is Nishiogi becoming a place people “want to know” that most threatens its contemporary identity as a town of small independent shops. The continued increase in population and developments around the station provides business opportunities but also challenges the human-scale urbanization we have seen up until now (James Farer, Fumiko Kimura, Jan. 29, 2018).

(translation by Asaki Shibutani and James Farrer; copyright James Farrer)

Appendix: Nishi-Ogikubo Urbanization Timeline

Here we have created a resource for understanding the developments in the neighborhood during the early twentieth century. It emphasizes the contributions of Uchida Hidegoro.

References

■ Me de miru Suginami-ku no 100 nen Kyoudo shuppansha Published on June 15, 2012 (Heisei 24)

■ Nishi-Ogikubo kankou techou Nishi-Ogikubo shoutengairengoukai Inohana Tokujyu“Nishiogi kankou techou” henshubu Nishiogi annaijyo Published on February 28, 2015 (Heisei 27)

■ Iogimura goudeshi Momoijinjyōkoutoushōgakkō Momoijinjyōkoutoushōgakkō rekishikenkyubu Published: June, 1914 (Taisho 14)

■ Suginamikyoudoshisousho3 Suginamifudoki jyokan Author: Mori Yasuji Suginamikyoudoshikai Published: June 30, 1977 (Showa 52)

■ Uchida Shugoro no kijyuwo syukushita shokanokongou Publisher: Uchida Shugoro kijyushokugakai Published: November 1, 1952 (Showa 27)

■ JR Chūō sen Machi to eki no 1 seiki Sairyusha Published: July 1, 2014 (Heisei 26)

■ Suginami no chizuwoyomu -Egakaretamono Kakusaretamono- Suginami-ku bunkyoushi hakubutsukan Published: October 26, 2002 (Heisei 14)

■ Yakushin no Suginami Nagumo Takekado ed. Suginamikouronsha Published: May 2, 1936 (Showa 11)

■ Chūōsen no uta ge Asahi Shinbum Tokyo Soukyoku Author: Miyazawa Atsushi Photo: Chiba Yasuyoshi First edition published on: June 14, 2006 (Heisei 18)

■ Bureikou no sake ni ts udou Garuvadosu no kai Author/Publisher: Ooshi Yoshiko Published: October 2015 (Heisei 27)

■ Ogikubofudoki Ibuse Masuji Shincho bunko First Published: April 15, 1987 (Showa 62) 12th Edition Printed: November 11, 2014 (Heisei 26)

■Seishutotomonijidaiwoikita Mitsuya saketen no meibutsuoyajigakataru Koyoiwadonomaigaraninasaremasuka Author: Kamoshida Souichiro Published: December 12, 2010 (Heisei 22)

■ Suginami-ku Chūōsenensenkasaihokenzu (kabu) Toshiseizushasakusei

■ Zenmenkoukyuchizu Tokyo Osaka Nagoya Zenjyutakuannaichizuchō Koukyoushisetsuchizukabushikigaisha Shibuya Itsuo Published: January 1, 1969 (Showa 44)

■ Nishiogi machiaruki mappu 2016 ban 2017 ban ©Nishiogi annaijyo

■ Suginami-ku no gaiyou https://www.city.suginami.tokyo.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/014/016/midorizittai24_02.pdf

■ Ogikubosho ho-mupe-ji Ogikubo 1-3choume no shozakai ga fukuzatsu ni irikunndeirunoha naze

http://www.keishicho.metro.tokyo.jp/4/ogikubo/why/why.htm#12

■ Suginamigaku kurabu https://www.suginamigaku.org/2010/11/nakajima-hikoki-3.html